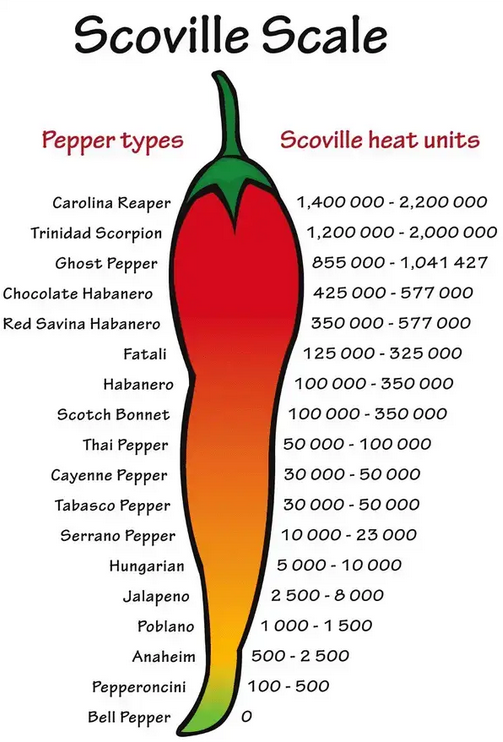

The Scoville scale, a measure of spice or spicy heat of chili peppers, is a popular way of quantifying heat intensity. It’s common to hear people reference the Scoville heat units (SHUs) when talking about the fiery kick of their favorite hot sauce or pepper. But when it comes to wasabi, a spicy condiment from Japan, there is often some confusion.

How Hot is Wasabi on the Scoville Scale?

Wasabi is not pepper and can not be on the Scoville scale. However, subjectively, it is hot from 2500 to 8000 SHU, delivering a sharp, sinus-clearing heat that dissipates rapidly, unlike the lingering burn of chili peppers. Commercial wasabi products from horseradish, mustard, and green food coloring contain little real wasabi and no spiciness.

The Scoville Heat Unit (SHU) is a standard measure of spiciness primarily associated with chili peppers and is based on the concentration of capsaicin, the chemical responsible for the spicy sensation. The claim that wasabi registers between 2,500 to 8,000 SHU, similar to the range of a jalapeño, is somewhat misleading. Real wasabi’s heat comes not from capsaicin but from isothiocyanates. The sensation experienced from wasabi is a sharp, sinus-clearing heat that notably differs from the prolonged burn associated with chili peppers. This heat from wasabi tends to hit suddenly and dissipates just as quickly.

Further complicating the matter is that many commercial “wasabi” products outside Japan often contain very little, if any, genuine wasabi. Authentic wasabi is derived from the rhizome of the Wasabia japonica plant, which is notoriously difficult to cultivate. Due to its scarcity and high cost, many manufacturers substitute real wasabi with a blend of ingredients that mimic its flavor and heat. This mix typically includes European horseradish, mustard, and green food coloring. These substitutes, particularly horseradish, provide a heat sensation somewhat reminiscent of real wasabi but is far less intense. When measured on the Scoville scale, these substitutes might register at a much lower SHU, sometimes less than 300, or even lack spiciness altogether, especially when contrasted against the claimed range for genuine wasabi.

Understanding the Scoville Scale:

Invented in 1912 by Wilbur Scoville, the Scoville Organoleptic Test involved diluting a pepper extract until its heat was no longer detectable to a group of tasters. The degree of dilution gave its SHU. Today, the method has evolved into high-performance liquid chromatography to determine capsaicin concentration. Capsaicin is the chemical responsible for the burning sensation we associate with chili peppers.

Wasabi: A Different Kind of Heat

Now, wasabi is an entirely different beast. First, it’s essential to note that the primary compounds responsible for the kick in wasabi are not capsaicinoids (like in chili peppers) but are instead isothiocyanates. The sensation you get from consuming wasabi is a sharp, sinus-clearing heat that dissipates rapidly, unlike the lingering burn of chili peppers.

Wasabi, known for its iconic green hue and potent kick, is a unique and intricate flavor experience beyond its fiery reputation. Here’s an in-depth look at the taste profile of wasabi:

1. Immediate Sharpness: Upon first taste, wasabi strikes the palate with an immediate sharpness, different from the gradual buildup of heat commonly found in chili peppers.

2. Sinus-Clearing Sensation: The most distinctive characteristic of wasabi’s heat is how it quickly travels up the nasal passages, delivering a sinus-clearing sensation. This nasal heat is due to the isothiocyanates in wasabi, which vaporize speedily and stimulate the nasal passages more than the tongue.

3. Short-lived Intensity: Unlike the lingering burn of many spicy foods, the intensity of wasabi is ephemeral. The sharpness peaks quickly and fades within moments, leaving only a mild, lingering warmth.

4. Earthy Undertones: Beneath the initial burst of heat, genuine wasabi has subtle vegetal and earthy notes akin to the taste of raw green vegetables or freshly cut grass. This nuance is a hallmark of fresh wasabi and is often lost in many commercial preparations.

5. Slight Sweetness: Wasabi has a faint hint of sweetness, which balances its fiery nature. This sweetness is more evident when consuming freshly grated wasabi rhizomes.

6. Bitterness: Wasabi can be slightly bitter in lower-quality or older preparations. Fresh wasabi has minimal bitterness but becomes more pronounced as it ages or is exposed to air.

7. Umami: Like many ingredients in Japanese cuisine, wasabi offers a touch of umami, the so-called “fifth taste” often described as savory. This umami quality can enhance the flavors of accompanying foods, particularly raw fish in sushi.

What About Commercial Wasabi Products?

It’s essential to note that many “wasabi” products outside Japan contain very little real wasabi. Instead, they’re made from horseradish, mustard, and green food coloring. Horseradish, like wasabi, contains isothiocyanates, so their heat profiles are somewhat similar. But again, comparing horseradish or wasabi to peppers on the Scoville scale would be like comparing apples to oranges.

Conclusion

The spice of wasabi and the heat of chili peppers like jalapeños are distinct experiences driven by different compounds. While trying and fitting everything spicy onto the Scoville scale is tempting, wasabi operates outside it. What’s clear is that both jalapeños and wasabi offer unique heat profiles that can be appreciated in their own right. Whether you’re looking for the lingering warmth of chili pepper or the sudden, nostril-tingling sensation of wasabi, there’s a world of spicy flavors to explore.

- How Many Tablespoons is One Clove of Garlic? - June 26, 2024

- How to Measure 3/4 Cup When You Don’t Have the Right Measuring Cup? - June 6, 2024

- How Much Does Cooked Pasta Weight Compare To Dry? - April 30, 2024